Cradle mountain, overland track

- hm

- Dec 21, 2025

- 13 min read

Updated: Jan 2

Roughly heart-shaped, Tasmania lies just south of Australia’s eastern coast — a rugged, green island known for wild weather, deep forests, and some of the country’s most rewarding hikes. I had heard about the Overland Track for years and finally decided to walk it in the middle of the Tasmanian summer.

Knowing that permits for the Overland Track are tightly limited, I checked the Tasmania Parks website and discovered that there was exactly one permit left for December — for a single hiker. I booked it immediately.

The permit arrived by email, accompanied by stern warnings about safety and the fickle, often harsh weather of Cradle Mountain. Watching the mandatory pre-hike videos was not reassuring. One in particular was downright grim, detailing just how quickly conditions can deteriorate and how unprepared hikers can get into serious trouble.

I emailed a few gear-rental companies and eventually settled on Paddy Pallin in Launceston. I reserved everything I needed and planned to pick it up a couple of days before the hike — a warm sleeping bag, tent, hiking poles, a 70-liter backpack, a cooking stove with gas, and a personal locator beacon. When I arrived, all of it was waiting, set aside and ready to go.

Launceston is one of Tasmania’s oldest cities and its second largest, and I was struck by how strong its outdoor culture is. Within a short walk, I counted seven or eight gear-rental and outfitter stores, all stocked with the latest equipment. Paddy Pallin carried a full range of dehydrated wilderness meals as well, which I bought to cover the six days on the track — with a few extra, just in case.

Launceston also surprised me with how good the food was. There’s a dense cluster of restaurants around town, and I ate well in the days leading up to the hike. I had hoped to visit Josef Chromy, one of the nearby wineries, but ran out of time. Meals at places like Mudbar, Earthy Eats, Tatler Lane coffee shop were standouts — simple, satisfying, and memorable in a way that stayed with me on the trail.

Launceston is a city of contrasts: a university campus, leafy parks, and streets lined with historic buildings. Many of the older structures feature intricate cast-iron work, giving the city a lot of character and a sense of history at every corner.

The morning the hike began, I woke at five, packed my gear, and waited for the 6:30 AM pick-up from the Overland Track Transport company. By 6:33, I was starting to wonder if I was in the wrong spot — but a minute later the shuttle turned the corner. Simon, the driver, was polite, friendly, and informative, immediately putting me at ease.

The shuttle carried three other passengers: Steve, hiking alone; and Donna and her husband, who planned to start their walk the following day. I later learned that Steve’s girlfriend had canceled her Cradle Mountain permit due to tendonitis — the very permit I had managed to grab, the only one available in December.

On the 100-kilometer ride to Cradle Mountain, we had a brief stop in Sheffield — a town famed for its 160 odd murals and annual mural festival, a tradition started to improve the local economy.

We arrived at the modern Cradle Mountain Visitor Center at 9:05 AM. My name was on the ranger's list, and a 30-minute briefing followed, complete with repeated warnings about the unpredictable weather. The ranger asked me to certify that I had the clothing and safety items required for survival.

I’d mapped out my daily walking plan with ChatGPT before the trip, and at the time it all looked pleasantly achievable — nothing that hinted at just how different things can feel once you’re out there in the Tasmanian wild. By now, I was beginning to feel that all the warnings and reminders about the Overland Track were a little overblown, maybe even excessively gloomy.

At one point, I even found a tiny walking map printed on the back of a freeze‑dried meal packet — and to my surprise, it matched the ChatGPT itinerary almost exactly. The packet also included a Sudoku puzzle, a small, unexpected gift to keep me occupied during the long, quiet stretches of downtime in the huts.

After the ranger briefing, I waited for the park shuttle bus - Cradle Discoverer - which ferries both day hikers and Overland trekkers to one of four trailheads.

The ride felt like the final transition from preparation to reality, and when the driver called out Ronny Creek, I stepped off with that quiet mix of anticipation and uncertainty that comes just before a long walk begins.

I signed the logbook at the trailhead. Now, it was time to tackle the Overland Track itself. True to its name, it is a track over the land — narrow, roughly 40 centimeters wide in places, reinforced with hexagonal wire mesh. The path stretched ahead as far as the eye could see, dotted with hikers already making their way with heavy packs.

Within minutes, Steve and I fell into step, and I reminded myself that I was expected to climb up to 4,000 feet today. My 21‑kilogram backpack felt heavy, but there was no one to complain to — and no way around it.

Steve had quickly become my “partner in crime.” He walked briskly ahead, and soon we reached the section known as Marion’s Lookout. The chains I had been warned about appeared on a steep, rocky stretch — sharp rocks, bolts, and a chain to aid climbers over about 25 meters of incline.

At the top, the view opened to a grand panorama. Many people were gathered, basking in the sunshine. Some hikers, clearly part of a high-end tour that cost upwards of AU$7,000, were sipping wine, a contrast that made me smile.

A little further along, we reached Kitchen Hut. Many hikers dropped their backpacks to attempt the side trip up Cradle Mountain itself — a sharp, rocky scramble of roughly 400 meters. The climb looked challenging, and I decided to skip it, content with the track itself.

For the next couple of hours, the trail grew quiet. Most people had taken the four-hour detour, leaving me on a lonely stretch of the Overland Track.

In the distance, I spotted a large dome-like structure, which I assumed was our hut for the night. It turned out, somewhat comically, to be an emergency shelter instead.

Six hours after setting out, I arrived at Waterfall Valley Hut. To my surprise, it was almost luxurious — modern, clean, and seemingly new.

A large rainwater-collection tank supplied cold, fresh water that tasted wonderfully pure. The toilets were spotless, housed in a separate building about 50 meters away, a small but very welcome touch after a long day on the trail.

On the second day, I started bright and early, savoring coffee at the hut before setting off at 7 AM. I said goodbye to Tom, the volunteer hut caretaker, and stepped out into calm weather after an overnight rain. The day’s hike was only 8 kilometers — one of the easier legs of the Overland Track — and at first, the trail felt quiet and manageable.

A few people passed me along the way, including Greg, his eight-year-old son Charlie, and their friend John. Soon, the weather turned dramatically. On the exposed sections of the track, hail pelted my cheeks, strong winds pushed me sideways, and sleet quickly turned into blizzard conditions. Charlie began to cry, but Greg stayed calm and patient; at one point, the little boy even developed a nosebleed.

Later in the day, we learned that Andrew had been knocked off the track by a gust of wind and split his forehead open. His daughter Eliza, along with fellow hikers Richard and Dianne, happened to be carrying stitch tape and managed to apply three neat strips to hold the wound together. It was a sobering reminder of how quickly things could turn out here.

Paddy Pallin had sold me a pair of possum‑hair gloves that were wonderfully warm — until the blizzard hit. Within minutes, they were soaked through, and my hands throbbed painfully from the cold.

I realized I had forgotten to cover my backpack. Everything inside became soaked. Snow clung to my clothing, and the wind was relentless. Relief washed over me when I finally reached Windermere Hut.

Paul, the caretaker, was friendly and helpful. The hut itself was modern and welcoming, with heating that worked in 45‑minute bursts and a large rainwater-collection tank providing fresh, cold water. I had brought Betadine tablets but didn’t like the taste, so I boiled a liter of rainwater, which was perfect. I ended up drinking two liters that day.

Because it was a short hiking day, most people had reached the hut by noon. The afternoon buzzed with stories of everyone’s struggles on the exposed Bluff, battered by snow and hail.

Steve, my hiking buddy — a podcast ad software developer from Montreal — shared stories alongside Greg, Charlie, and John from Hobart; Tiffany and Jane from Brisbane; Jim, Katrina, and young Madeline from Melbourne; Jane and David, doctors from Melbourne with their son Patrick; Hyung, a solo hiker from Seoul; Andrew and Eliza from Canberra; Richard and Dianne from Darwin; and a group of seven 22-year-old university students. Altogether, 23 of us occupied the hut, which could accommodate 34.

The hut was modern, roomy, and cozy. I arrived at 9:30, with a full day to enjoy the heated comfort. Outside, snow fell intermittently, sometimes heavy enough to make the world feel frozen in white. The group of young hikers couldn’t resist — snowball fights broke out, laughter echoing across the clearing. I took the opportunity for a much-needed two-hour nap, letting the warmth of the hut restore my energy for the days ahead.

The park service had done a great job in describing the flora and fauna, terrain, and route distances. At Windermere, a large signboard laid it all out: elevation profile, track surface, weather warnings, even a reminder to maintain salt and sugar levels. It was oddly reassuring, in part a trail guide, and a survival manual. There were notes on the buttongrass plains, rainforest textures, and even the sound of the Tasmanian Thornbill. It felt like the kind of briefing that wanted you to notice everything, not just endure it.

Day three, December 15, I began early. I woke at 5 AM to steady snowfall, the path to the bathroom already covered in white. After hot coffee and packing, I was ready to leave by 7, until I couldn’t find my navy-blue rain jacket. I searched everywhere, and others joined in to help. Eventually, it turned up, inside out, exactly where I had already looked.

Steve and I set off together at 7:20 AM for the longest day of the hike — 16.8 kilometers. Snow fell steadily, the wind cut hard, and sleet turned into blizzard conditions. My new shoes went from damp to soaked, and gusts pushed us off the narrow, 45-centimeter-wide track. In places, snow covered both the path and the triangular markers on the trees. A couple of times we walked in circles before finally rediscovering the route and pressing on.

By 1:30 PM, I reached Pelion Hut, the midpoint of the Overland Track and the end of its longest day. I felt a quiet sense of relief. Back when I first read the warnings about hikers dying on this trail, I’d assumed they were exaggerated, maybe even a touch theatrical. But after two days of snowstorms, sleet, and blizzard conditions, I understood why those cautions existed. I was glad to have made it through. Part of me wondered if the hike would’ve been more enjoyable with perfect weather like on day one, but I eventually settled on the thought that the past two days, with all their challenges, had made the journey more interesting, more demanding, and ultimately more satisfying.

A couple of hikers had spotted a tiger snake along the track close to the hut, on the track's wooden board, and it slithered away when they approached. I hadn’t seen one myself, though I secretly hoped I would. The park’s first aid posters made it clear that Tasmania’s snakes are venomous but shy, and the advice was oddly specific: don’t panic, retreat slowly, and never try to kill the snake for identification. It felt like the kind of encounter that would add a dash of drama to the hike, just enough to make it memorable, not dangerous. I kept my eyes peeled, half hoping for a glimpse, half relieved I didn’t get one. I was carrying a snake bandage in case things got serious, and the gaiters on my shoes were worn religiously each day, a quiet nod to caution even as I scanned the trail, half hoping for a glimpse, half relieved I didn’t get one.

On the other hand, a mother wallaby and her joey spent a good half hour frolicking on the track right in front of the hut, a gentle reminder that not all wildlife encounters needed to come with an adrenaline spike.

December 16 took us to Kia Ora Hut — a Māori name — over a relatively shorter 10-kilometer day with about 300 meters of climbing. Steve and I left again at 7:20 AM under light hail, but the weather steadily improved as the morning went on.

Along the way, we met Lillian from the Tasmanian Hiking Company, who for eight years was walking the trail in summer supporting her clients and working in the huts over the winters, and now dreaming of becoming a park ranger. She carried an enormous 80-liter backpack with quiet determination.

We spotted pademelons along the trail and reached the junction for Mount Ossa and Pelion East, where the views opened up beautifully. The currawong birds were bold here, unzipping packs and stealing unattended items, and the climb stretched to around 400–500 meters in places. Ninety minutes later, we arrived at what felt like the newest hut on the track.

Joel, the caretaker, was busy cleaning and making repairs. I met John, 57, hiking with his young son Frankie — John mentioned he was the only one among four friends his age still walking long distances like this.

As I sat enjoying the view of cathedral mountain, the Melbourne family of James, Katrina, and Madeline passed through and continued on to the next hut; we later realized we would all end up on the same 9:30 AM ferry from Narcissus Hut on the 18th. The group of seven 22-year-old hikers attempted Mount Ossa and Pelion East, though some turned back when the snow deepened near the summit.

I cooked Thai chicken for lunch and mushroom Bolognese for dinner, sharing chocolate and extra food with others. The sun stayed out all day, and for the first time in a while, there was no rain at all.

On day 5, I was up at 5:30 AM and packing when I realized I’d run out of coffee. Steve came to the rescue with an extra coffee sachet. I set water to boil and continued packing, only to return five minutes later to find the burner off. The gas canister, brand new and supposedly good for 55 boils, was completely empty after just seven. Disappointing, to say the least. Tiffany saved the morning by lending me her gas cylinder, and I finally had my coffee.

For the sub‑10‑kilometre hike to Windy Ridge (also called Burt Nichols), we set off around 8 AM. It turned into a beautiful, sunny day. Although the coffee and a protein bar had got me started, an hour later I was hungry again and grateful for a hefty 90-gram bar I had kept within easy reach.

We soon found ourselves walking through what felt like an enchanted forest. The track was laced with thousands of exposed tree roots, beautiful in their own way, but treacherous if your foot slipped between them, the kind of hazard that could turn into a serious injury in seconds. I was glad I had my hiking poles to arrest my fall multiple times.

About ninety minutes into the walk, we reached the waterfalls. I visited the first, took a few photos, and then realized the second was just around the corner. It was massive and genuinely impressive, a powerful reminder of how much water this landscape can move.

The short hike from the waterfalls to Windy Ridge included a 350‑metre climb up Du Cane Gap, and the accumulated fatigue of the past few days made that stretch feel longer and steeper than it looked on the map. The descent on the other side was no easier — a sharp drop threaded with sprawling, thick tree roots that created huge step‑downs and demanded full concentration.

Eventually we reached the old‑looking hut with its dark interior, a welcome sight after the effort. Once I’d set up my bunk, I ended up chatting with Hyang from Seoul. We shared a meal in the sunshine outside, both of us quietly pleased that the hardest parts of the hike were behind us and that the rest of the afternoon was ours to simply sit, talk, and enjoy doing nothing at all.

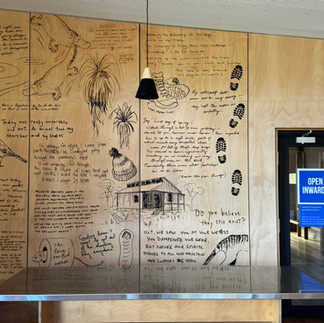

After a while, Patrick, David, and Jane began reading aloud poems and haikus that hikers had written in the logbook over the years. Jane quickly authored a poem about the hike and the blissful absence of phones and modern apps like Instagram and Snapchat, a surprisingly funny take on going off‑grid.

I leafed through the notes, sketches, stories, and verses left behind by past walkers, and somewhere in that quiet, sunlit moment felt inspired to try something I’d never done before: write my own haiku. Here’s what came out:

New shoes, excited to walk

Overland Track, full of snow

Slipping every minute.

Reaching huts, tired and hungry

Pelion, Windermere, Kia Ora

So modern and pretty.

Aussie, Kiwi, and Canadian

Tall, short, thin, wiry

All greet: “How are you going?”

Shoes, socks, jackets

All muddy and wet

Everyone hogs the heater space.

Ossa, Pelion, Cathedral

High, pretty mountains

Some climb, some of us watch.

Steve had more time in his schedule, but he decided to join me for the final day’s walk to Narcissus Hut. We agreed on a 5:15 AM start for the 9‑kilometre stretch, a quiet pre‑dawn pact to make the 9:30 AM ferry to the Lake St Clair visitor center. The track notes said it would take three to four hours, and with a ride to Hobart booked for 2 PM, catching that ferry wasn’t optional. It added a small, steady undercurrent of urgency to an otherwise gentle final morning.

The track that morning was beautiful, soft forest light, bursts of flowers, and occasional mountain views opening up between the trees. We made brisk progress to the suspension bridge and soon reached Narcissus Hut. Inside was the old phone used to call the ferry, and I checked in to confirm my pickup. They even had space for Steve. With the hard walking behind us, we waited by the jetty, watching platypuses ripple across the lake — a quiet, almost magical way to end the journey.

The ferry arrived like clockwork, the pilot both cordial and quietly informative as he helped us aboard. With the lake perfectly still and the mountains reflected in the water, the thirty‑minute ride to the visitor center felt like a gentle glide back into the world.

The moment we stepped off the boat, I made a beeline for the café, after days of dehydrated meals, the promise of real food was impossible to resist.

In the four‑hour wait for the Hobart shuttle pickup, we all sat around chatting, taking photos, and exchanging contact details. Stories flowed easily, mishaps, favorite moments, future plans, and soon we were trading ideas for possible adventures around the world.

It felt like the natural closing chapter of the hike: a small circle of people who had shared the same weather, the same huts, the same track, now lingering together before scattering back to our own lives.

I was glad to have done this hike. It demanded a surprising amount of planning and execution — flights and ferries, shuttles and luggage storage, gear rental and food supplies, permit acquisition and constant weather monitoring, but every bit of it was worth it.

I made new friends, saw landscapes I’ll remember for years, and spent six days immersed in nature on an island tucked beneath the continent down under. It felt like a journey that asked a lot but gave even more in return.

Wonderful adventures, you make one want to follow in your footsteps